Understanding and supporting the health of minority ethnic people

How we can develop a more holistic way of thinking about health and care with community groups impacted by Covid-19? Kay Olivierre kickstarts the conversation with health and care practitioners to develop meaningful improvements.

It is well known now that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities have been, and continue to be, disproportionately impacted by Covid-19. As Baroness Doreen Lawrence wrote; “We are in the midst of an avoidable crisis.”

The government’s own review, published by Public Health England in June this year, points to a number of reasons for this. It found that Covid-19 has exacerbated long standing social and economic inequalities which already existed.

Individuals from BAME groups are more likely to work in occupations with a higher risk of Covid-19 exposure, and are also more likely to use public transportation to travel to their essential work. The pre-existing health conditions that increase the risk of having severe infection (such as having underlying conditions like diabetes and obesity) are also more common in BAME groups.

Racial discrimination affected people’s life chances pre Covid-19, but the review also pointed to racism and discrimination experienced by communities, and specifically by BAME key workers, as a root cause affecting health, exposure and disease progression risk. The stress caused by being discriminated against based on race/ethnicity is detrimental to both mental and physical health. But BAME communities are less likely to seek care when needed, waiting until crisis point, and COVID-19 has exacerbated that issue. The stigma of COVID-19 has negatively impacted how BAME groups take up opportunities to get tested and seek early care.

There a number of factors which have led to BAME communities being disproportionately affected by Covid-19, many of them societal, cultural and economic. The healthcare profession can’t solve all of these, but there are aspects it is well placed to deal with. And, for me, the answer lies in looking at causes of stress for these communities, as mentioned in the government’s review.

This light-hearted “Class System” sketch from 1966 may not have much resonance now but the message on the slide, shown during a lecture on cancer last year, jumped out at me.

Stress affects everything. It impacts mental health, causes depression, anxiety, weight gain, chronic illness and even wrecks academia/work performance. It can even weaken the immune system in ways that many people do not know until years later, if they survive viruses such as Covid-19.

Many academic papers point to stress having substantially damaging impacts on physical and mental health. In her 2010 paper for the Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, “Stress and Health: Major Findings and Policy Implications” Peggy A Thoits synthesises 40 years of stress and health research which demonstrate how stressful events have substantial damaging impacts on physical and mental health.

She states that differential exposure to stressful experiences is a primary way that ‘racial-ethnic’ and social class inequalities in physical and mental health are produced. She also claims that ‘minority’ group members are additionally harmed by stress related discrimination, and that stresses proliferate over the life course and across generations, widening health gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged group members.

For me, then, this raises the wider question of whether the stress of belonging to a particular ethnic group in itself should be deemed a wider determinant of health?

For me, then, this raises the wider question of whether the stress of belonging to a particular ethnic group in itself should be deemed a wider determinant of health? And, if so, how do we support healthcare professionals to recognise and tackle this, as well as empowering people within these communities to be responsible for their own health-related behaviours?

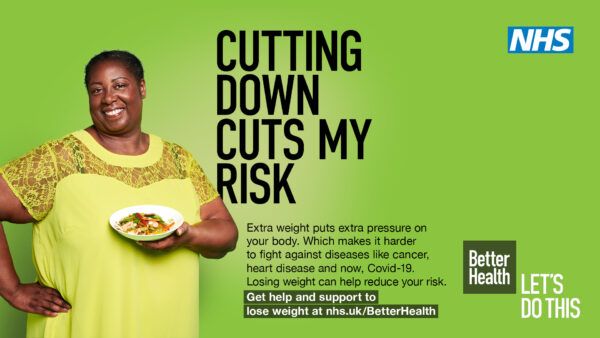

This is an advert from the NHS, which is part of a public campaign to help weight loss amongst overweight BAME women. Clearly, the system is well meaning and constantly trying to seek out ways to help ladies such as the one in this advert.

However, in order to do that, I believe health professionals need to take a holistic approach, which understands the stress factors impacting on BAME communities, in order to deliver better healthcare. They need to support these communities to be better informed about their own health, putting them in the driving seat, improving their own self-esteem and empowering them to consider their own health decisions.

This drives a different conversation between BAME patients and health and care professionals, where patients are more informed and take more responsibility for their own health. Peggy Thoits’ research paper confirms the correlation between health literacy and health-related quality of life in patients with a range of chronic diseases. She also points out that the impact of stress on health and well-being are reduced when people have high levels of mastery, self-esteem and social support.

The BBC series, ‘Doctor In the House’, featuring Midlands GP Dr Rajan Chatterjee, demonstrates this holistic approach to health really well. He has turned himself into what I call a ‘roaming functional practitioner’ who visits peoples’ homes and looks at every aspect of their lives, to help them improve their health and well-being. GPs have neither the time or resource to do this with every patient, but I do believe his message needs to be taken seriously by everyone. He is empathetic and wholehearted in his role. He takes into account people’s lifestyle and what matters to them and their families, in order to help them mitigate the causes of disease and prevent future issues across the generations via education and encouraging them to lead by example.

This is known as “functional medicine”, when the whole person is treated (physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually), not just their physical ailment. People are listened to and treated holistically, taking into consideration all the aspects of their life, both positive and negative impacts. Patients treated in this way are also encouraged to take more responsibility for their own health.

The government’s review makes a number of recommendations to help improve healthcare for BAME communities. But for me, it begins with education for healthcare professionals. It is vital that medical education is re-examined and co-designed with a diverse range of patient advocates. Healthcare professionals need to be more aware of the impact of belonging to a BAME community as a health determinant and be enabled to better holistically support these patients.

We also need to bring all stakeholders together to have a sensible debate about the place that functional – or holistic – medicine has within the NHS. We have made a start on this with social prescribing, but COVID-19 has shown there is a long way to go. At Imperial College Health Partners (ICHP), we engaged with nearly 100 BAME healthcare professionals, faith leaders, community leaders and citizens as part of our Community Voices project, looking at the impact of COVID 19 on BAME communities. One of their key calls was for a “paradigm shift” in the relationship between frontline professionals and BAME communities, enabling patients to feel more empowered.

If we are genuinely committed to delivering integrated care that puts patients at the heart of everything we do, then – for me- taking a holistic approach to healthcare is the only way forward.

If we are genuinely committed to delivering integrated care that puts patients at the heart of everything we do, then – for me – taking a holistic approach to healthcare is the only way forward. One which puts tackling inequality at its heart, and a genuine desire to recognise and tackle the multitude of issues which can cause poor health amongst BAME communities.

So, my question for melting pot attendees today is, how can we make this a reality? How can we ensure this happens across the new integrated care systems across the country, and what can you do within your sphere of influence?

The issues raised in this blog will be part of the discussion with Kay at our online Melting Pot Lunch on 12 November.

Kay Ollivierre9 November 2020

Kay Ollivierre9 November 2020

Comments