Living with a long-term health condition: a journey of one day at a time

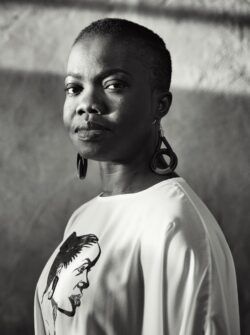

When you have lived with a chronic health challenge for over two decades, you can safely say it is a burden many of us would rather not bear. Belinda Otas talks about her journey and the importance of psychosocial care and support when navigating the difficulties of long-term conditions.

My health journey began in 1995, at the age of 15, and nothing could have prepared me for all that has happened to my body, my mind and my life as it is today. It started with typhoid fever, which soon morphed into debilitating migraines.

A year later, after a series of medical missteps in Nigeria, I ended up with end-stage renal failure at 16. I lived on dialysis from the age of 16 to 22. During this period, I don’t remember ever having a conversation with anyone about what was happening to me. I was told I needed dialysis, so I showed up for each session. It never dawned on me that I needed psychological support. Mind you, I didn’t know enough about renal failure, and certainly knew nothing about mental health or its complexities. I didn’t even have the emotional awareness that my spirit and inner child was hurting.

I knew I was in physical pain. I was aware that dialysis three times a week drained me. Yet, I didn’t have the language to express the knots in my stomach or the pain that ached my soul. Now when I look back, I remember being grateful to be alive, and that remains the case. I also remember the frustration of feeling like a spectator in the story of my life and watched on as time went by, yet had no control over the events unfolding. It is painful when your teenage years, the formative years of one’s life are snatched from you and you feel powerless to do much about it.

My late mum was my saving grace during the first iteration of my dialysis experience. She was my rock and did everything for me. I was also blessed with a close group of friends who were very understanding and helpful. Some of them are still with me today.

My life has gone through many changes since 1996, when I started dialysis. I had my first transplant at 22. A life changing experience which gave me the ability to get my life back on track. I was finally able to do some of the things on my goals list like go to university, and travel home to Nigeria to see my family. My first transplant served me for 15 years, and I’m incredibly grateful to my donor and their family for saying yes to organ donation.

In 2012, I had an acute rejection episode. Once again, nothing prepared me for the havoc my body would endure when what you trust to keep you safe, your own body, rejects a transplanted organ. With care and medication, high dose of steroids and other immunosuppressants, the renal team that looks after me managed to keep me off dialysis for another five years. In the interim, while we waited with bated breath to see how well my transplanted kidney would recover from the rejection episode, I was reactivated on the transplant list. My kidney did recover little by little, as my kidney function gradually improved over a five-year period.

I have since come to understand a kidney transplant is not a cure for kidney disease. It is better than being on dialysis, and it comes with responsibilities. The biggest of which is to look after yourself. Be militant and regimental in approach with your medication. You cannot afford to slip up and give your body any ammunition to reject or attack an organ that will always be foreign to it, and as such let you down. You have to take care of yourself and your body, so it can take care of you.

In July 2017, I had my second kidney transplant. It was a pre-emptive transplant to stop me going back on dialysis. However, the second time around was not a magical experience. Despite the best efforts of the medical team looking after me, this particular transplant came with its own baggage. Soon enough, the hospital became my second home, and after months of trying to save the kidney a decision was made to do a re-transplantation to help improve my graft function. Unfortunately, this did not work. So, it went from being a re-transplantation to a radical nephrectomy (The first of the three nephrectomies I had in a space of three years). By January 2018, I was back on dialysis.

Being back on dialysis has been incredibly difficult and painful. To be in this position in my late 30s, through my early 40s was not something I envisioned. Again, I have had to reposition my life, and this time around without my mother. A loss, which upon reflection in my current circumstance, I can’t put into words.

Significantly, in the five years, I have been back on dialysis, I have also come to a better understanding about the dynamics and difficulties of living with a long-term chronic illness and how it shapes and shifts your life. I do not consider myself to be a medical expert. What I do know, and have, is my experience. At a time when the NHS is heavily oversubscribed and stretched, healthcare must become more than a call/visit to the GP, hospital referrals/treatment and pills. As a dialysis patient, I believe our care needs to be more than having dialysis because healthcare is multidimensional. As we witness the struggles of the NHS to meet increasing demand, we have to figure out other ways to deliver wholesome care that helps us to live a much more enriched and full life, even with long-term health challenges.

Recently, I heard the word ‘Psychosocial’ in a renal patient’s meeting. It was used by Fiona Loud, Policy Director at Kidney Care UK, as she talked about the Psychosocial Care Manifesto, Kidney Care had developed for people with kidney disease. Though I may have heard this word before, on this occasion, and based on the explanation Fiona gave about the purpose of the manifesto, it deeply resonated with me. Because I finally had the language to describe the inclusive type of care that would be most helpful to patients like myself who live with a chronic illness.

Let me put my hands up and admit I’m still learning about the different parts that constitute psychosocial care/support. This is where Google becomes a girl’s best friend. So, I went searching and found a paper, What is Psychosocial Care And How Can Nurses Better Provide It To Adult Oncology Patients, by Melanie Jane Legg (RN, GradCertPH, GradDip Nursing Science – Oncology), a registered nurse at St Andrews Hospital, South Australia. The definition it gives – Psychosocial support involves the culturally sensitive provision of psychological, social and spiritual care (Hodgkinson 2008) – succinctly captures what I believe is useful to patients like me. I also agree with Kidney Care UK that “Psychosocial care is recognised as a key element of person-centred care.”

It is my opinion that if this becomes a key component of the care designed for people with chronic long-term health challenges, in a way that empowers and champions the independence of patients based on the level of medical attention they need, we stand a better chance of more positive outcomes. For this to happen, psychosocial support needs to be one of the foundational building blocks of our care, not an afterthought.

For context, “3.5 million people in the UK have chronic kidney disease. 30,000 people live on dialysis, and every day, 20 people develop kidney failure. One in three patients with kidney disease will experience depression. Yet, none of the 84 renal units in the UK employs the recommended number of social workers for their kidney patient population, while only five percent employ the recommended number of psychologists for their patients,” according to Kidney Care UK. If the trajectory of these numbers continue as they are, the NHS in its current state will most certainly buckle and fail more people than it helps.

We cannot minimise the impact of psychosocial care on our physical, mental and emotional health, social and cultural circumstances, and yes, our spiritual life, to the degree that you may have one or believe in a greater power than yourself.

The establishment of this crucial support at the beginning, or at any point of our long-term health challenge, not only empowers us to have the language to express the distress we feel; it also allows us to reposition ourselves to make intentional decisions about our health in a way that serves us well.

It will allow us an opportunity to gain a better understanding of the nature of our diagnosis, its symptoms and the treatment we need. It will also aid our ability to get to a place of acceptance. With acceptance, comes the ability to set realistic life goals that are attainable. This will help us to stay motivated with a sense of accomplishment.

We will also understand the need for self-care that includes healthy daily habits. I must stress the importance of adhering to your prescribed diet. If you are a renal patient, you know this means staying away from salt, keeping your potassium and phosphate levels low and being very strict with your fluid allowance. Equally, it will be of great help to take up exercises suitable for your condition, and develop stress management techniques like meditation to help you cope on the days when life gets crazy. And without a doubt, engage in activities allows you to escape into a world that brings you some joy. For me, this includes art gallery and theatre visits.

It will also stand us in good stead to develop and build a supportive network. From our family members to our friends, who have an understanding of some of our health needs. We must also learn to communicate our needs and concerns. People can only help when they know what you need. We cannot underestimate the importance of a reliable support network and its ability to alleviate stress and provide emotional strength.

Understanding some of the limitations our long-term health challenges imposes on our lives is critical to managing our expectations. This is a continuous process that includes repositioning our lifestyle, work, and daily activities to accommodate our health needs. We also have to learn to adapt because sometimes, our long-term health challenges imposes physical limitations on us which can lead to disappointments in ourselves. Hence, we have to embrace adaptability which involves seeking out alternative health solutions, the use of assistive devices, or learning new skills to enhance our independence.

It also helps to connect with other people dealing with similar health challenges. Exchanging knowledge, sharing experiences and learning from each other can be empowering because you realise you are not alone, and you are not imagining things. What you are feeling is real and that’s okay too. All of this, in addition to the power of gratitude and learning to celebrate our daily small victories will make a great difference to our long-term health challenge journey.

One thing that was of great help to me in 2018 as I struggled with my new reality was the support of the renal psychology team. However, this support is not readily available to everybody because resources are limited.

After 27 years of a long-term health condition: 11 years of dialysis, two kidney transplants, three nephrectomies, chronic pain, depression and other challenges along the way, what I know for sure is that it is a thief of time. That’s one of the biggest things I have lost. I also know it is a damn difficult reality. And there are days when you cannot “positive think” your way out of a funk. There have been days when my greatest achievement was being able to get out of bed, go to the bathroom, clean up and back to bed.

I do not have all the answers for how to improve long-term or chronic health challenges. However, it is my hope that as we learn more about our individual health challenges and psychosocial care and support, we will seek out tools that help us manage better and regain the freedom of our time. And more than surviving daily, we also thrive to the degree our individual circumstances allows, and we can push ourselves to attain.

Join Belinda for a free online Fresh Conversation on Wednesday 17 May.

Belinda Otas15 May 2023

Belinda Otas15 May 2023

Comments